This is part eleven of my Judges study. Read the previous parts here and watch for part twelve coming on November 20.

Chapter 11 tells most of the story of Jephthah, the second-last major judge. We are told that he was a valiant warrior, the son of Gilead (though “Gilead” was probably not his father’s actual name)1 and a prostitute and that his legitimate half-brothers drove him out. Upon fleeing to the land of Tob, he joined a group of “worthless men,” (literally translated as “empty men”) essentially a criminal gang, with which he went on raids.2 Ironically, Tob means “good,” and Jephthah was certainly not doing good there!3

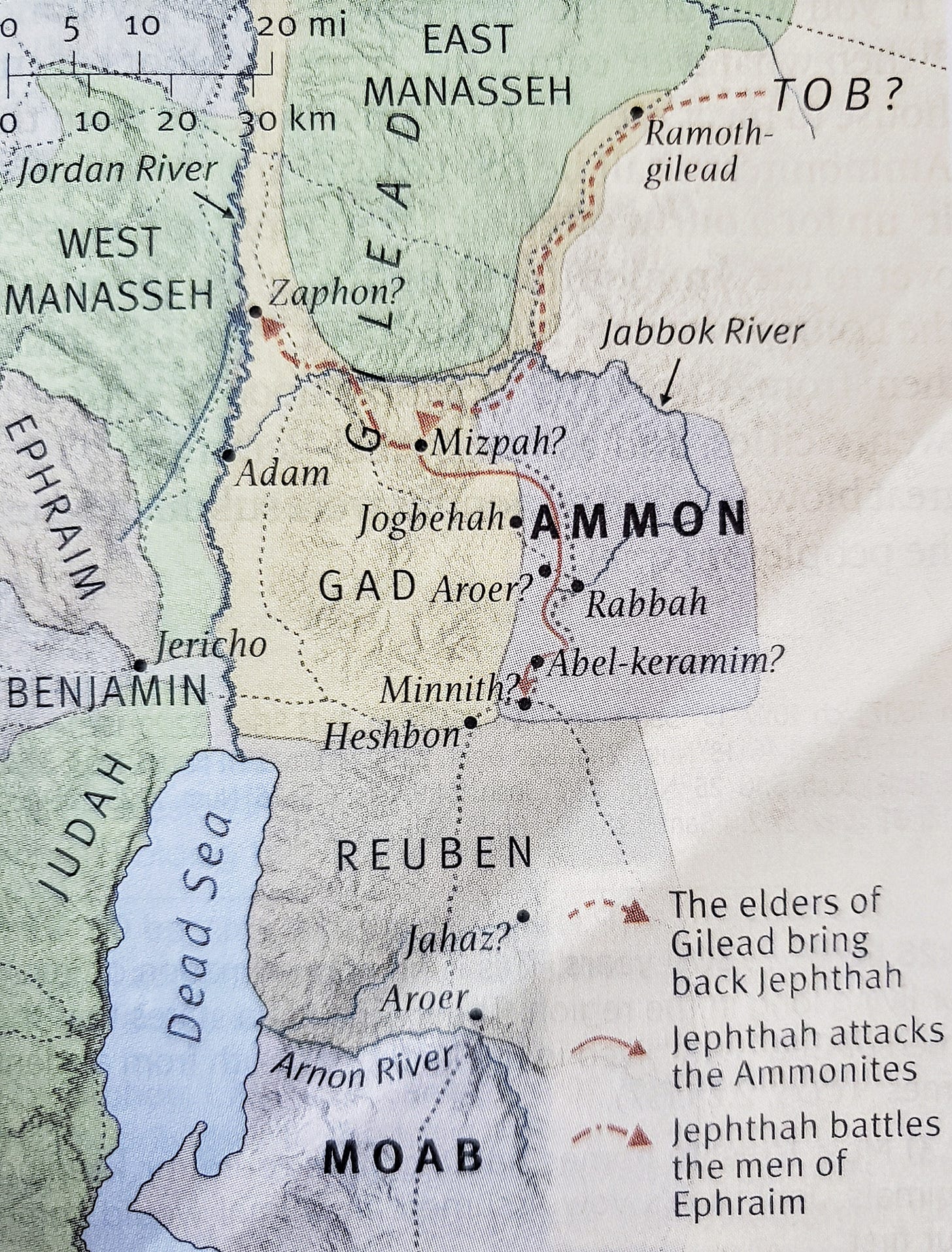

Sometime later, the Ammonites went to war with Israel and the elders of Gilead offered to make Jephthah their commander if he fought alongside them. Jephthah was understandably still bitter about having been disowned by his family and gave an angsty response: “Didn’t you hate me and drive me out of my father’s family? Why then have you come to me now when you’re in trouble?” The elders of Gilead basically said, “Well, yeah, we did. But hey, we need your help, bro. You can be our leader of all Gilead!” Then, Jephthah agreed to go and became their leader. Two different words were used, so while they originally offered Jephthah a leadership position in battle, they extended this to a higher and more long-lasting one.4 Interestingly, the situation between Jephthah and the Gileadites parallels the common pattern of the book of Judges between God and Israel, as Barry G. Webb has noted below.

The next portion of the chapter constitutes a series of communications between Jephthah and the Ammonites. First, Jephthah asked the Ammonite king why he was fighting against Israel. The Ammonite king responded by saying that after the exodus, the Israelites took a portion of Ammonite land and he wanted it back. This contested land was bordered by three rivers: the Arnon, Jabbok, and Jordan.5

Jephthah’s next communication was a longer one in which he stated that Israel had not taken land from the Ammonites. He explained how the Israelites had asked to travel through Edom and Moab but were denied access, and travelled around instead. The Israelites had camped on the other side of the Arnon and also sent a message to the king of the Amorites, Sihon, in which they requested permission to travel through his land. Instead of allowing them to travel, Sihon sent his army out to fight Israel and the Amorites were defeated, so the Israelites took over the land between the Jabbok and the Arnon. These examples of Israel’s past conduct with the Moabites, Edomites, and Amorites were meant to illustrate that the Israelites did not take anyone’s land unjustly and were innocent of the charges placed upon them by the Ammonite king.

After recounting all of these events, Jephthah’s message continued with a bit of an unhinged rant. He went on about how the Israelites should be able to keep the land that God gave them, just as the Ammonites can have whatever land their god Chemosh conquers for them. Next, he asked a rhetorical question in which he asked if the king of the Ammonites was better than Balak, king of Moab, who never contended with Israel. Jephthah said that if the Ammonites wanted their land back so badly, why had they not taken it during the three hundred years Israel had resided there? Because he had not sinned against them, the Ammonites were doing wrong by initiating a conflict with Israel, and God would judge between the Israelites and Ammonites.

Unfortunately for him, Jephthah was a bumbling idiot who had no idea what he was talking about. His letter is riddled with errors and massive face-palm moments for those who have a passing knowledge of biblical history. There is a great YouTube video from my favourite channel that I have linked below which I suggest watching if you would like to get a better understanding of some of the issues in this difficult and frequently misunderstood passage, as he explains it much better than I ever could.

Israel had indeed sent messengers to the king of Edom, requesting to pass through his land, as recorded in Numbers 20:14-21. Nothing of this sort is related for Moab, so Jephthah may have made that part up but it could also have happened and not been recorded in the Pentateuch. The incident with Sihon of the Amorites is found in Numbers 21:21-24 and went as Jephthah said it did.

Things get really wild in the last part of his letter. First of all, Chemosh was the god of the Moabites, not the Ammonites! The Old Testament mentions this on various occasions in Numbers 21:29; 2 Kings 23:13; and Jeremiah 48:13, 46. Ammon’s main god was Milcom, as attested elsewhere in the Bible such as in 1 Kings 11:5, 7, 33; 2 Kings 23:13; and Jeremiah 49:1. Jephthah also has a faulty theological view in thinking that the gods of other nations have the power and authority to conquer land for those who worship them. His question regarding Balak was very misguided, as Balak did in fact contend with Israel, something Jephthah does not seem to have been aware of. Balak literally, and I mean literally, recruited Balaam to put a curse on Israel, so he most certainly contended with them! We read in Numbers 22:5-6:

he [Balak] sent messengers to Balaam son of Beor at Pethor, which is by the Euphrates in the land of his people. Balak said to him, “Look, a people has come out of Egypt; they cover the surface of the land and are living right across from me. Please come and put a curse on these people for me because they are more powerful than I am. I may be able to defeat them and drive them out of the land, for I know that those you bless are blessed and those you curse are cursed.”

Further, we are later told, “Balak son of Zippor, king of Moab, set out to fight against Israel” (Joshua 24:9), and even though this was not a physical battle, he still was an enemy of Israel who wanted to see them defeated.

It is in the midst of these numerous errors that Jephthah said the Israelites had been living in the cities on the banks of the Arnon for three hundred years. This verse (26) has been used endlessly by those holding a 15th-century BCE date of the exodus, as they believe in a longer period of the judges than those who accept the 13th-century BCE date. Unfortunately for them, this verse is no evidence at all because, as we have already established, Jephthah had no idea what the hell he was talking about. See my previous posts about the date of the exodus for more information, because the early-daters are experts in taking things out of context and this is a big problem.

Jephthah’s question regarding why the Ammonites had not attempted to take back their land is again inaccurate because they had tried to get it back a few other times previously in the book of Judges. In Judges 3:13, the Ammonites and Amalekites had teamed up with the Moabites to attack Israel and took some of their land. Similarly, the Ammonites oppressed Israel for eighteen years as seen in Judges 10, which we looked at last month.

The Spirit of the Lord came upon Jephthah and he vowed that if he succeeded in vanquishing the Ammonites, he would offer as a burnt offering to the Lord the first person or animal who came out of his house when he returned victorious. Then, Jephthah crossed over to the Ammonite lands, fought against them, and defeated twenty of their cities. Upon returning to his home in Mizpah, Jephthah’s daughter and his only child came out to congratulate him with music and dancing. These tambourines that she is said to have playing would have been made of animal skin stretched over a wooden ring.6 When he saw her, Jephthah became distraught and tore his clothes because of the vow he had made. Since this daughter was his only child and it was customary for women to celebrate a victory with instruments and dance, it is unclear why he was so surprised when she exited the house, though he clearly was.7

The wording used in this vow is ambiguous, as reflected by differing English translations. Some use “whoever,” whereas others use “whatever.” Although the latter is slightly more well-attested in translations, the former has more textual and grammatical support, especially given the phrase “to greet/meet me.”8 Given all this, Jephthah probably had a human sacrifice in mind, attesting to the depravity of not only his character but the time of the judges in general.

His daughter told him to do as he had vowed but requested two months to wander with her friends and mourn the fact that she would die a virgin. After the two months had passed, Jephthah sacrificed her to the Lord and it became an annual custom for the young women of Israel to remember the short and tragic life of this unnamed biblical figure.

There has been some debate as to whether or not Jephthah actually sacrificed his daughter, as the text does not directly state that he had her killed. These people interpret the passage as her having become a lifelong virgin in service to the Lord, as she is said to have mourned her virginity and not the loss of her life. However, it does specify that “he kept the vow he had made about her,” and the vow clearly said that he would offer a burnt sacrifice, so I do not think there is a good case to be made that she was not killed.

Additionally, there is no indication in the Old Testament that virginity was especially important in serving God, and having the two months of weeping take place before Jephthah’s vow was fulfilled is completely unnecessary if her death was not imminent.9

Since I chose this passage for an assignment in Bible college, I thought I would share what I wrote for that project below. Aside from my frequent misspellings of “Jephthah” (which I have fixed), it is actually a pretty good assessment of the text and I still affirm what I wrote in it. Enjoy this 887-word segment from some of my writing in 2022!

Why did Jephthah make a vow to sacrifice whatever came out of his house? The first time I heard this story as a child several years ago, [someone]10 explained that people kept animals in their house, and Jephthah had expected one of them to come out. However, that explanation never satisfied me because I could not logically make sense of it. Would not Jephthah have expected his daughter to come and greet him after his military victory? Futhermore, if his animals could exit the house whenever they wanted, what would stop them from wandering away completely? This explanation had many plotholes, yet I believed it for so long because it was the only answer that I was given.

Looking at the original language can help modern-day readers better understand confusing yf Bible passages; this is certainly the case in verse 31. The Hebrew words hayotze asher yetze, often translated as “whatever comes out” can also mean “whoever comes out,” as shown in a few translations (RSV, CSB, NRSV, NET, CEV).11 Additionally, “the Hebrew word liqrati, translated here as ‘to meet me,’ literally means ‘towards me,’ implying intelligence and intent, which also seems to suggest that Jephthah’s expectation was that the ‘whatever’ would be human.”12 Based on this information, it is reasonable to conclude that Jephthah was not expecting an animal to come out of his house, but rather a human. Victor P. Hamilton wrote, “It is unlikely that Jephthah anticipated that, upon returning home from battle, he would be met by a servant or some kind of animal… Thus, for Jephthah, who better than his daughter to come out and meet him after eliminating the Ammonites?”13

This situation is further complicated by the fact that the text says that “the Spirit of the Lord came upon Jephthah” (Judges 11:29), just one verse before his vow. Arthur E. Cundall observed that “first, Jephthah, by the coming of the Spirit of the Lord upon him, became a charismatic hero, empowered by God to effect the deliverance of his people. But then, in the second place, he showed his lack of appreciation of the character and requirements of the Lord, and also a lack of confidence in the divine enablement, by seeking to secure the favour of God by his rash vow.”14

Sometime during the Middle Ages, an interpretation of this passage arose saying that Jephthah did not actually kill his daughter but forced her to live a life of celibacy.15 This is not supported by a direct reading of the text, which clearly says that Jephthah “kept the vow he had made” (Judges 11:39). Since he had vowed to sacrifice whatever or whoever came out of his house as a burnt offering, there is no reason to believe that this did not happen. Jewish tradition agrees with this interpretation [that Jephthah’s daughter was indeed sacrificed], as shown in the writings of Josephus and the Talmud.16

However, some argue that Jephthah paid the specified amount in Leviticus 27:2-7 instead of sacrificing his daughter.17 More support for this explanation is found in the other biblical references to Jephthah, 1 Samuel 12:11 and Hebrews 11:32, both of which paint him in a positive light and mention delivering Israel from its enemies. They say that it is not possible for the killing of Jephthah’s daughter to have taken place, due to the way in which he is presented in these verses. Jephthah did indeed gain a victory over the Ammonites, as described in verses 32-33 of Judges 11, so these verses are not wrong even if one takes the position that he did sacrifice his daughter.

The verse in Samuel mentions Gideon and possibly Samson, both judges who, like Jephthah, helped Israel achieve a military victory, yet had some sort of dysfunctional family situation. This verse does not mean that these men were good examples for the people to follow, but that they were used by God to eliminate the threat of other nations. Hebrews says very little about Jephthah, similarly grouping him in with five other individuals and all the prophets. Gideon and Samson are mentioned here as well, proving that this verse is not claiming that the people listed there lived moral lives.

In light of all of this, it is very likely that Jephthah was expecting a human, possibly even his daughter, to come out to meet him after his victory over the Ammonites. The text indicates that he later regretted making this vow, although he failed to acknowledge that this was his mistake, and instead accused his daughter of bringing disaster on him. Cundall’s words illustrate the consequences that led to Jephthah’s regret of making his vow. “The fact that Jephthah’s daughter bore no child was more than a tragedy of a life unfulfilled… It represented the termination of the clan of Jephthah himself, since she was his only child.”18 Jephthah was probably selfishly motivated in making his vow, perhaps looking for human recognition. His blaming of his daughter, who was innocent in this matter, for destroying him makes no sense logically. At this point, Jephthah was too afraid to own up to his actions. After his daughter returned from her two months in the hills, he followed through with his vow and dealt with the reality of what he had done by unjustly placing the guilt on his daughter.19

What Jephthah was probably unaware of is that the Torah contains instructions regarding what to do if one has made a rash and sinful vow. It was something that could be atoned for by making a sin offering, as seen in Leviticus 5:4-13:

Or if someone swears rashly to do what is good or evil—concerning anything a person may speak rashly in an oath—without being aware of it, but later recognizes it, he incurs guilt in such an instance.

If someone incurs guilt in one of these cases, he is to confess he has committed that sin. He must bring his penalty for guilt for the sin he has committed to the Lord: a female lamb or goat from the flock as a sin offering. In this way the priest will make atonement on his behalf for his sin.

But if he cannot afford an animal from the flock, then he may bring to the Lord two turtledoves or two young pigeons as penalty for guilt for his sin—one as a sin offering and the other as a burnt offering. He is to bring them to the priest, who will first present the one for the sin offering. He is to twist its head at the back of the neck without severing it. Then he will sprinkle some of the blood of the sin offering on the side of the altar, while the rest of the blood is to be drained out at the base of the altar; it is a sin offering. He will prepare the second bird as a burnt offering according to the regulation. In this way the priest will make atonement on his behalf for the sin he has committed, and he will be forgiven.

But if he cannot afford two turtledoves or two young pigeons, he may bring two quarts of fine flour as an offering for his sin. He must not put olive oil or frankincense on it, for it is a sin offering. He is to bring it to the priest, who will take a handful from it as its memorial portion and burn it on the altar along with the food offerings to the Lord; it is a sin offering. In this way the priest will make atonement on his behalf concerning the sin he has committed in any of these cases, and he will be forgiven. The rest will belong to the priest, like the grain offering.

Obviously, Jephthah was a very deeply flawed person. He should never have made the vow in the first place, as not only did he fail to specify that it had to have been a ritually clean animal, but the making of the vow was an attempt to bribe God into giving him what he wanted. Yes, he ended up gaining a victory over the Ammonites, but he suffered a much bigger loss due to his foolishness and plain stupidity. Even so, if he had known the Torah, he could have given a sin offering instead as human sacrifice is repeatedly condemned and never commanded in the Bible.

As I promised in last month’s Judges post, this one is certainly longer! In fact, it is the longest Bible study post I have written so far. I really appreciate those who read the whole thing, as it took many hours of researching and writing to end up with the final result.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Block, Daniel I. “Judges.” In Joshua, Judges & Ruth, edited by John H. Walton, 198-451. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009.

Boda, Mark J. “Judges.” In Judges, Ruth, edited by Tremper Longman III and David E. Garland, 30-347. The Expositor’s Bible Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012.

Cundall, Arthur E., and Leon Morris. Judges and Ruth. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries Series. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008.

Evans, Mary J. Judges and Ruth. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries Series. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2017.

Hamilton, Victor P. Handbook on the Historical Books: Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra-Nehemiah, Esther. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2001.

Landers, Solomon. “Did Jephthah Kill His Daughter?” Bible Review 7:4, (August 1991). https://www.baslibrary.org/bible-review/7/4/15. Accessed March 20, 2022.

Magonet, Jonathan. “Did Jephthah Actually Kill His Daughter?” The Torah, 2015. https://www.thetorah.com/article/did-jephthah-actually-kill-his-daughter. Accessed March 20, 2022.

McCann, J. Clinton. Judges. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Preaching and Teaching Series. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 2011.

Way, Kenneth C. Judges and Ruth. Teach the Text Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2016.

Webb, Barry G. The Book of Judges. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament Series. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012.

Younger Jr., K. Lawson. Judges and Ruth. The NIV Application Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002.

Webb, The Book of Judges, 317.

Younger, Judges and Ruth, 241.

Webb, The Book of Judges, 317.

Boda, “Judges,” 225.

When I read “Arnon,” I thought “oh yeah, isn’t that some kingdom of men in Middle-Earth founded by Elendil or something?” Then I looked it up and no, the kingdom is actually called “Arnor.” But it is confusing, as only the last letter is different! Also, Jabbok just makes me think of Jabberwocky because I’m weird like that.

Block, “Judges,” 331.

McCann, Judges, 93.

Webb, The Book of Judges, 335; Evans, Judges and Ruth, 126.

Evans, Judges and Ruth, 128.

It feels dumb censoring my writing when I did not even name anyone here, but I really cannot afford to make enemies of whoever was mentioned ATM, so censorship it is.

Landers, “Jephthah Kill His Daughter?” Online.

Ibid.

Hamilton, Handbook on Historical Books, chap. 2, section: H. Jephthah (10:6-12:7), Kobo ePub.

Cundall, Judges and Ruth, 142.

Ibid., 144.

Landers, “Jephthah Kill His Daughter?” Online.

Ibid.

Cundall, Judges and Ruth, 143.

Magonet, “Did Jephthah Actually Kill?” Online.

I really enjoyed this Rachel, especially that segment of your assignment.

I never quite realized how disturbing that thing with Jephthah's daughter is. I love your research and open minded presentation of possibilities.

Thanks for sharing this 🙏

Lots of interesting stuff happened in the time of the judges! I appreciate all the work you put into these posts. Why did you choose this book to study?