Judges Chapter 8 Bible Study

Gideon does some flesh tearing, killing, idolatry and polygamy

This is part eight of my Judges study. Read the previous parts here and watch for part nine coming on August 21. It is a less-known part of Judges because it is not a nice story, so I hope this post refreshes your memory if you have not read the chapter in a while!

The chapter begins with the men of Ephraim becoming angered with Gideon because he did not call them to fight until after his army started the battle and chased away the Midianites. They took offence at this, though it is unclear whether Gideon wanted to provoke them, forgot about them, or had some other reason for not calling the Ephraimites.1 Gideon expertly handled the situation, replying that Ephraim had the greater role as they had killed the Midianite princes, and their anger faded. His grape metaphor “Is not the gleaning of Ephraim better than the grape harvest of Abiezer?” is used to say that although his clan Abiezer acquired the full harvest of Midianites, the gleanings left behind representing Oreb and Zeeb were the best part of it.2

Then, Gideon took his 300 men across the Jordan and requested bread from the men of Succoth. However, the men of Succoth refused to provide him with bread as he had not yet killed the Midiantie kings Zebah and Zalmunna. Their question literally translates to “Are the palms of Zebah and Zalmunna now in your hand?” because cutting off the hands of war captives was a common practice in the ancient Near East to count how many enemy soldiers had been defeated.3

As a result, Gideon exclaimed that he would tear the flesh of the men of Succoth with thorns once he had killed Zebah and Zalmunna. Next, he and his men travelled to Penuel, where Jacob wrestled with God (Genesis 32:24-32), where they once again asked for bread and were denied it, so he promised to tear down the tower there when he came back.

At this point, the narration briefly explained the situation that Zebah and Zalmunna were in. The two kings were in Karkor with the remaining 15 000 men, as 120 000 had been killed. While they were there, Gideon attacked their army and pursued Zebah and Zalmunna until he captured them.

Upon returning from the battle, Gideon took a young man from Succoth and had him write down the names of the city’s 77 leaders and elders, using what would have been an early alphabetic script and either ostraca or animal skins.4 Gideon headed back to Succoth, showed the men of the city that he had captured the Midianite kings, and disciplined them with thorns and briars. Then he tore down the tower of Penuel and killed the men of the city. This destruction of the tower foreshadows an event in the next chapter.5 The brutal slaughter and mutilation of fellow Israelites at Succoth and Penuel is a clear example of Gideon’s thirst for vengeance.6 Nowhere in the text does God command such actions, and they stand in stark contrast to prior revelations.

Zebah and Zalmunna told Gideon that the men they had killed at Tabor looked similar to him, like sons of a king. Gideon announced that these men were his brothers and if Zebah and Zalmunna had not killed them, he would let the kings live. However, he sought to enact vengeance upon them and told his firstborn son, Jether to end the lives of the Midianite kings.

Jether was young and too fearful to kill them, so Gideon did so himself when they taunted him. Asking one’s son to do the killing would have been seen as an honour and a way for the next generation to learn fighting skills.7 Interestingly, Jether in this passage is a sort of parallel to the Gideon of chapter 6, as both are characterized by fearfulness.8 Then Gideon took the crescent ornaments from Zebah’s and Zalmunna’s camels. There is an ancient Near Eastern depiction of camels wearing jewelry on a monument of the Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser III.9

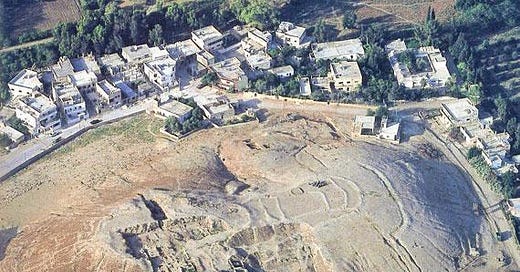

After all this, the Israelites asked Gideon to be their ruler, along with his descendants. He refused but asked each person to give him a gold earring from their plunder, as they had fought the Ishmaelites who wore gold earrings. Gideon used the gold from the earrings and the crescent ornaments to make an ephod which he set up in his hometown of Ophrah, where “all Israel prostituted themselves” (Judges 8:27). What began as a small, localized cultic site was transformed into a place of idolatrous worship for the whole nation.10

An ephod is mentioned in Exodus and Leviticus as something to be worn by the high priest, associated with the Urim and Thummim.11 In this passage, however, its usage is portrayed negatively. Gideon’s ephod was likely a garment designed to be worn by a statue of a deity, violating the command not to make or worship idols.12 It has been suggested that the term “ephod” here not only refers to this garment but also acts as a sort of euphemism for the image on which it was placed.13

The last portion of the chapter summarizes the rest of Gideon’s life. He had 70 sons by many wives and a son named Abimelech from a concubine in Shechem. Ironically, Shechem was the place where the Israelites promised to follow God and not worship idols.14 Gideon lived a long time and was buried in his father's tomb. After his death, the Israelites worshipped Baal and did not remember the Lord or show kindness to the house of Gideon.

If Chapter 7 was the high point of Gideon’s story, Chapter 8 chronicles his downfall. After achieving a great victory with the help of God, he went from being cowardly to overconfident and antagonistic. As such, this is not the kind of story people like to tell. It is a tale of both humanity’s failure and wasted potential and how the people used by God in the Bible did some nasty things.

In the end, Gideon failed as a judge and although he declined the offer to become a king, he certainly acted like one. His statement that neither he nor his son will rule over Israel is further made ironic by the actions of his son Abimelech, as we will see later on.15 Additionally, the fact that he named his son Abimelech (meaning “my father is king”) indicates that he had an inflated sense of self-importance and behaved arrogantly.16

As you can probably guess, I get annoyed when people make Gideon into a hero. They often justify this position by referencing Hebrews 11:32, a verse that names Gideon in a list of prominent Old Testament figures. Unfortunately, Hebrews 11 is a passage that has long been misinterpreted as being about “heroes of the faith” when that was not the author’s intent. While all these people exercised faith in God and were used by him, the entire chapter builds toward Jesus, as “God had provided something better for us” (Hebrews 11:40).

Kenneth Way does an excellent job of explaining why this sort of reasoning is faulty exegesis:

[T]o argue on the basis of Hebrews 11 that the book of Judges therefore provides behavioural role models for Christians to imitate would be to put aside more objective hermeneutical methods and impose a more subjective reading on the text of Judges that ignores authorial intentions.17

In summary, Judges 8 does not make Gideon look good. His story marks the beginning of the bad judges in the book’s downward spiral, and things only get worse from here. It is Bible passages like this that demonstrate that people who have accomplished great things in the name of God such as famous Christian pastors, apologists, and evangelists can sometimes let the fame get to them and become total jerks. A good lesson to take from this is not to put people on a pedestal, as they will always mess up and can influence people in harmful ways.

If you have been reading these Judges posts from the beginning, thank you for your faithful readership! I am passionate about helping people understand commonly misunderstood or less well-known parts of the Bible, so it means a lot that others are getting something out of this. Please subscribe to help me out if you have not!

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Block, Daniel I. “Judges.” In Joshua, Judges & Ruth, edited by John H. Walton, 198-451. Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009.

Boda, Mark J. “Judges.” In Judges, Ruth, edited by Tremper Longman III and David E. Garland, 30-347. The Expositor’s Bible Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012.

Evans, Mary J. Judges and Ruth. Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries Series. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2017.

McCann, J. Clinton. Judges. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Preaching and Teaching Series. Louisville, KY: John Knox Press, 2011.

Way, Kenneth C. Judges and Ruth. Teach the Text Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2016.

Webb, Barry G. The Book of Judges. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament Series. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012.

Younger Jr., K. Lawson. Judges and Ruth. The NIV Application Commentary Series. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2002.

Webb, The Book of Judges, 260.

Boda, “Judges,” 190.

Block, “Judges,” 303.

Ibid., 304-305.

Younger, Judges and Ruth, 194.

McCann, Judges, 79.

Webb, The Book of Judges, 268.

Younger, Judges and Ruth, 195.

Way, Judges and Ruth, 114.

Webb, The Book of Judges, 276.

Way, Judges and Ruth, 115.

Block, “Judges,” 308.

Younger, Judges and Ruth, 201.

Evans, Judges and Ruth, 103.

Way, Judges and Ruth, 119.

Ibid.

Ibid., 123-124.